Reducing Design Risk

Reducing Design Risk

Eric Olive 2020-05-07T10:30:00+00:00

2020-05-07T12:37:25+00:00

Lean, agile, do more with less. Again, and again, design culture urges us to move quickly and trim research and design operations to the point where design becomes a mere thread in the larger corporate spool.

Author and designer Nikki Anderson explains the consequences of this pressure to conduct research at lightning speed:

“When we’re asked to synthesize at the speed of light, user research becomes a way for teams to take a shortcut — to invent assumptions based on quickly made correlations, opinions, and quotes.”

The result is design based on assumptions or incomplete information about users and customers. For example, a Fortune 500 company (let’s call it Company Q) hired me to conduct a usability test for a complex user interface (usability testing involves a series of one-on-one sessions with real users who are asked to complete specific tasks while using a product or piece of software).

The test yielded what would likely become recognizable patterns, and I was halfway through the analysis when I was ordered to pause and send the client the findings immediately. My explanation about the need for more time to conduct a thorough and nuanced analysis fell on deaf ears:

“Just send a short video.”

I reluctantly sent a video snippet showing a participant struggling with the user interface (UI).

There was no time for background, context, or nuance. The product manager at Company Q recognized the participant in the video from a previous encounter and dismissed his struggles:

“He’s a crank, we can’t base decisions on him.”

The company moved forward without addressing this serious UI issue.

This product manager had become emotionally attached to his product (see endowment effect below). This emotional attachment hindered his ability to assess the product’s strengths and weaknesses objectively. It’s not surprising that professionals develop strong feelings about their products.

Understandable, but also problematic. As UX guru Jared Spool explains in an article about the ROI of UX, dismissing user needs carries a high cost:

For example, say you get many support calls because the design doesn’t do something the users expect. That’s a high cost due to a poor design decision.

How costly? According to Jeffrey Rumburg of HDI, the average cost of a single support call in North America is $15.56. Even if support calls only increase by 83,000 each month, the annual cost is over $15 million.

In contrast, addressing design problems works. According to the McKinsey report, “The Business Value of Design”:

“One online gaming company discovered that a small increase in the usability of its home page was followed by a dramatic 25 percent increase in sales.”

Note: For this study, McKinsey tracked the design practices of 300 publicly listed companies over a five-year period in multiple countries and industries. Their senior business and design leaders were interviewed or surveyed. The McKinsey team collected more than two million pieces of financial data and recorded more than 100,000 design actions.

These numbers demonstrate the direct financial costs associated with rushing market research and shortchanging user and customer concerns. They also illustrate the financial benefit of addressing customer concerns.

In this article, I’ll shed light on the techniques for addressing these concerns:

- Carefully selecting a research location;

- Compromising with stakeholders to allow sufficient time for analysis without delaying the design process;

- Making sound, evidence-based design decisions;

- Engaging in design reduction.

1. Context Over Convenience: Why Location Matters

Where you conduct research matters as much as the research method. Before booking a facility for your next user interview, consider the importance of location. You might not want to book a quiet meeting room if users work in a noisy environment with numerous distractions. In fact, the user’s environment will help you identify the best research method for gathering insights (interviews, diary studies, observation/contextual inquiry, usability tests, cognitive walkthroughs, etc.).

This is precisely what happened when our team conducted UX research for a manufacturer of large construction equipment. We could have brought machine operators to a quiet showroom to ask them questions about the equipment and what did and did not work well.

This would have been the easy but incorrect choice. Instead, we traveled to construction sites in the U.S., Mexico, and Colombia where we observed operators using the equipment outside where it was dusty, dirty, and loud.

On-the-ground observations included:

- Risks of vehicle collisions due to noise and low visibility when winds were high.

- The difficulty shorter operators encountered when reaching for certain controls in the cab (operators in Latin America were, on average, smaller than their U.S. counterparts).

- The rapid corrosion of metal equipment caused by salt on a construction site near the ocean.

Observing users in their real-world work environment:

- Reduced the risk of solving the wrong problem because we did not rely on second-hand information from sales or product (this happens more often than you might think).

- Allowed us (the researchers) to hear the noise, see the dust, and feel the bumps while riding on these enormous machines.

- Provided actionable insights that could not have been gathered in an office.

Our research at sites in Mexico and Colombia demonstrated the truth of the old adage. Meeting users where they worked every day yielded rich, qualitative data that our client used to inform important design decisions.

2. Compromise

This was a good outcome. The fieldwork in Mexico and Colombia identified real-world problems, and stakeholders acted on this information.

This is not always the case. There is a temptation to make design decisions quickly based on incomplete information as happened to Walmart when management decided to change aisle and shelving design based on a customer survey. When customers were asked if stores were too cluttered, they said yes. Walmart spent millions re-designing stores only to lose more than $1 billion in revenue. When Walmart reverted to the cluttered aisles, sales increased. What happened?

Two reasons for this fiasco were likely a poorly worded survey and incomplete analysis. Walmart relied too heavily on what customers said rather than what they did. The importance of placing considerable weight on what users and customers do is a bedrock principle in customer and user experience.

“Rather than just ask shoppers what they think they would like, I can follow someone through their shopping trip in a grocery or mass merchandise store like Walmart and Sam’s Club and then interview them as they load their bags into the car. What is striking is the wide gap between what they say they did, and what I observed.”

— Paco Underhill, author of Why We Buy. New York Times Article about Walmart.

Underhill, a legend in consumer and market research, is exactly right. Unfortunately, even when stakeholders agree to fund observation (ride-alongs, shop-alongs, contextual inquiry), there is considerable pressure to move forward the moment a UX or market study is done leaving little time for thorough analysis.

The goal in these situations is to strike a balance between speed and thoroughness. Product managers and other stakeholders have a great deal of responsibility and are often under pressure to move products to market quickly. Rushing the design process, however, can result in overlooking key user needs emerging from research.

Compromise during the transition from research analysis to design serves two purposes. First, it allows researchers sufficient time to review, reflect, and report accurate and actionable findings that will help the design team move forward. Second, as with any endeavor, a willingness to compromise establishes a degree of trust.

3. Better Design Decisions

Compromise and trust are a sound basis for establishing a constructive relationship between researchers, designers, and stakeholders. Such relationships contribute to an environment conducive to better design decisions. These points seem straightforward, even obvious.

Straightforward perhaps but not easily achieved. Why? Human nature. Humans are subject to what psychologists call the endowment effect, the tendency to overvalue objects you own simply because they belong to you. Selling a house is a classic example. As the homeowner, you are emotionally attached to your house because you’ve put effort into maintenance and improvements. The house holds fond memories. After all, you live there. None of this matters to the buyer. She only cares about the objective market value and getting the best house for the least amount of money.

Once the endowment effect takes hold, it’s difficult for people to part with the object, a house in this example. In the context of design, changing a UI or physical product is roughly equivalent to parting with it.

For example, while evaluating a complex UI for a programmable logic controller, the product manager announced to me and a room full of stakeholders: “My name is Jim, and I love this product.” Points for honesty. As expected, when I delivered the report, Jim held firmly to his belief that the UI was fine and did not require modification. He was, understandably, attached to the machine and the UI. Unfortunately, the company’s customers did not share this attachment as illustrated by ongoing customer complaints.

The data supports this conclusion. According to the McKinsey report mentioned above: “Less than 5 percent of those we surveyed reported that their leaders could make objective design decisions.”

The endowment effect is one of many barriers to making sound design decisions. See A Designer’s Guide To Better Decisions to learn how to avoid other, common decision traps.

Awareness of the endowment effect and other decision traps contributes to better design because it allows us to make tough choices during the actual design process.

4. Design Reduction

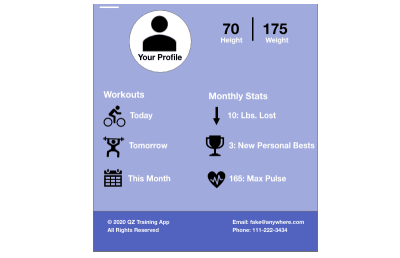

One such choice is what to remove from an existing design or an early design iteration. For example, the image shown below left could easily be an early iteration of a mobile app.

Few will argue against the power of simple, elegant, and engaging design. Such successes are often the result of careful, thoughtful reduction. From the number and size of elements on the screen to the simplicity or complexity of the color palette, it all comes down to reducing the design to the point that it’s clean and easy to use without removing anything essential.

Even in the cleaner example (above right), a designer might ask if “This Month” and “165: Max Pulse” are necessary. If not, removing them would be yet another reduction.

The point is not to debate the UI details for this fake fitness app. Rather, designers must anticipate the “everything-but-the-kitchen-sink” effect and make the case for removing unnecessary design elements. Effective techniques include:

- Gently reminding stakeholders and other team members about the risks of a heavy cognitive load.

- Sharing cluttered designs (any app or site will do) with the team and asking them to quickly locate a specific feature. Their struggle to find the feature will make the point.

- Sharing video clips of past research projects for your company showing how easily users become confused when interacting with a crowded UI.

Adhering to this reduction technique early in the design process benefits the business by decreasing the chance of user confusion, task or cart abandonment, and unhappy customers.

Design reduction is essential to creating engaging, user-centered design but only works when coupled with rigorous user research that contributes to informed design decisions.

Conclusion

Because research, decisions, and the design process go together, the focus of this article has been to identify the risks of rushing user research and design. Mitigating this risk does not require doubling the size of research and design teams. Instead, we’ve proposed four practical techniques that teams can implement immediately:

- Context over convenience

Location matters. Whether at home, a café, or on a noisy construction site, conduct UX and market research where users will be when interacting with your product. - Compromise

When business stakeholders cannot simply wait for a thorough analysis, compromise. At the stakeholder’s direction, the design team can move forward with limited design changes while agreeing not to make major changes until the final research analysis is complete. - Better design decisions

Make better decisions by keeping an eye out for the all-too-human tendency to become attached to a design you have created. - Reduction

Remove unnecessary UI elements leaving only what is necessary for users and customers to complete the task at hand.

(ah, yk, il)

From our sponsors: Reducing Design Risk