Introducing The Component-Based API

Introducing The Component-Based API

Introducing The Component-Based API

Leonardo Losoviz

2019-01-21T13:00:21+01:00

2019-01-21T12:14:45+00:00

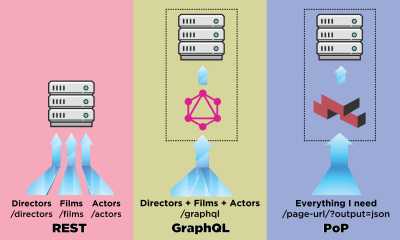

An API is the communication channel for an application to load data from the server. In the world of APIs, REST has been the more established methodology, but has lately been overshadowed by GraphQL, which offers important advantages over REST. Whereas REST requires multiple HTTP requests to fetch a set of data to render a component, GraphQL can query and retrieve such data in a single request, and the response will be exactly what is required, without over or under-fetching data as typically happens in REST.

In this article, I will describe another way of fetching data which I have designed and called “PoP” (and open sourced here), which expands on the idea of fetching data for several entities in a single request introduced by GraphQL and takes it a step further, i.e. while REST fetches the data for one resource, and GraphQL fetches the data for all resources in one component, the component-based API can fetch the data for all resources from all components in one page.

Using a component-based API makes most sense when the website is itself built using components, i.e. when the webpage is iteratively composed of components wrapping other components until, at the very top, we obtain a single component that represents the page. For instance, the webpage shown in the image below is built with components, which are outlined with squares:

The page is a component wrapping components wrapping components, as shown by the squares. (Large preview)

A component-based API is able to make a single request to the server by requesting the data for all of the resources in each component (as well as for all of the components in the page) which is accomplished by keeping the relationships among components in the API structure itself.

Among others, this structure offers the following several benefits:

- A page with many components will trigger only one request instead of many;

- Data shared across components can be fetched only once from the DB and printed only once in the response;

- It can greatly reduce — even completely remove — the need for a data store.

We will explore these in details throughout the article, but first, let’s explore what components actually are and how we can build a site based on such components, and finally, explore how a component-based API works.

Recommended reading: A GraphQL Primer: Why We Need A New Kind Of API

Ahoy! The hunt for shiny front-end & UX treasures has begun! Meet SmashingConf San Francisco 2019 🇺🇸 — a friendly conference on performance, refactoring, interface design patterns, animation and all the CSS/JS malarkey. Brad Frost, Sara Soueidan, Miriam Suzanne, Chris Coyier and many others. April 16–17. You can easily convince your boss, you know.

Check the speakers ↬

Building A Site Through Components

A component is simply a set of pieces of HTML, JavaScript and CSS code put all together to create an autonomous entity. This can then wrap other components to create more complex structures, and be itself wrapped by other components, too. A component has a purpose, which can range from something very basic (such as a link or a button) to something very elaborate (such as a carousel or a drag-and-drop image uploader). Components are most useful when they are generic and enable customization through injected properties (or “props”), so that they can serve a wide array of use cases. In the utmost case, the site itself becomes a component.

The term “component” is often used to refer both to functionality and design. For instance, concerning functionality, JavaScript frameworks such as React or Vue allow to create client-side components, which are able to self-render (for instance, after the API fetches their required data), and use props to set configuration values on their wrapped components, enabling code reusability. Concerning design, Bootstrap has standardized how websites look and feel through its front-end component library, and it has become a healthy trend for teams to create design systems to maintain their websites, which allows the different team members (designers and developers, but also marketers and salesmen) to speak a unified language and express a consistent identity.

Componentizing a site then is a very sensible way to make the website become more maintainable. Sites using JavaScript frameworks such as React and Vue are already component-based (at least on the client-side). Using a component library like Bootstrap doesn’t necessarily make the site be component-based (it could be a big blob of HTML), however, it incorporates the concept of reusable elements for the user interface.

If the site is a big blob of HTML, for us to componentize it we must break the layout into a series of recurring patterns, for which we must identify and catalogue sections on the page based on their similarity of functionality and styles, and break these sections down into layers, as granular as possible, attempting to have each layer be focused on a single goal or action, and also trying to match common layers across different sections.

Note: Brad Frost’s “Atomic Design” is a great methodology for identifying these common patterns and building a reusable design system.

Brad Frost identifies five distinct levels in atomic design for creating design systems. (Large preview)

Hence, building a site through components is akin to playing with LEGO. Each component is either an atomic functionality, a composition of other components, or a combination of the two.

As shown below, a basic component (an avatar) is iteratively composed by other components until obtaining the webpage at the top:

Sequence of components produced, from an avatar all the way up to the webpage. (Large preview)

The Component-Based API Specification

For the component-based API I have designed, a component is called a “module”, so from now on the terms “component” and “module” are used interchangeably.

The relationship of all modules wrapping each other, from the top-most module all the way down to the last level, is called the “component hierarchy”. This relationship can be expressed through an associative array (an array of key => property) on the server-side, in which each module states its name as the key attribute and its inner modules under the property modules. The API then simply encodes this array as a JSON object for consumption:

// Component hierarchy on server-side, e.g. through PHP:

[

"top-module" => [

"modules" => [

"module-level1" => [

"modules" => [

"module-level11" => [

"modules" => [...]

],

"module-level12" => [

"modules" => [

"module-level121" => [

"modules" => [...]

]

]

]

]

],

"module-level2" => [

"modules" => [

"module-level21" => [

"modules" => [...]

]

]

]

]

]

]

// Component hierarchy encoded as JSON:

{

"top-module": {

modules: {

"module-level1": {

modules: {

"module-level11": {

...

},

"module-level12": {

modules: {

"module-level121": {

...

}

}

}

}

},

"module-level2": {

modules: {

"module-level21": {

...

}

}

}

}

}

}

The relationship among modules is defined on a strictly top-down fashion: a module wraps other modules and knows who they are, but it doesn’t know — and doesn’t care — which modules are wrapping him.

For instance, in the JSON code above, module module-level1 knows it wraps modules module-level11 and module-level12, and, transitively, it also knows it wraps module-level121; but module module-level11 doesn’t care who is wrapping it, consequently is unaware of module-level1.

Having the component-based structure, we can now add the actual information required by each module, which is categorized into either settings (such as configuration values and other properties) and data (such as the IDs of the queried database objects and other properties), and placed accordingly under entries modulesettings and moduledata:

{

modulesettings: {

"top-module": {

configuration: {...},

...,

modules: {

"module-level1": {

configuration: {...},

...,

modules: {

"module-level11": {

repeat...

},

"module-level12": {

configuration: {...},

...,

modules: {

"module-level121": {

repeat...

}

}

}

}

},

"module-level2": {

configuration: {...},

...,

modules: {

"module-level21": {

repeat...

}

}

}

}

}

},

moduledata: {

"top-module": {

dbobjectids: [...],

...,

modules: {

"module-level1": {

dbobjectids: [...],

...,

modules: {

"module-level11": {

repeat...

},

"module-level12": {

dbobjectids: [...],

...,

modules: {

"module-level121": {

repeat...

}

}

}

}

},

"module-level2": {

dbobjectids: [...],

...,

modules: {

"module-level21": {

repeat...

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Following, the API will add the database object data. This information is not placed under each module, but under a shared section called databases, to avoid duplicating information when two or more different modules fetch the same objects from the database.

In addition, the API represents the database object data in a relational manner, to avoid duplicating information when two or more different database objects are related to a common object (such as two posts having the same author). In other words, database object data is normalized.

Recommended reading: Building A Serverless Contact Form For Your Static Site

The structure is a dictionary, organized under each object type first and object ID second, from which we can obtain the object properties:

{

databases: {

primary: {

dbobject_type: {

dbobject_id: {

property: ...,

...

},

...

},

...

}

}

}

This JSON object is already the response from the component-based API. Its format is a specification all by itself: As long as the server returns the JSON response in its required format, the client can consume the API independently of how it is implemented. Hence, the API can be implemented on any language (which is one of the beauties of GraphQL: being a specification and not an actual implementation has enabled it to become available in a myriad of languages.)

Note: In an upcoming article, I will describe my implementation of the component-based API in PHP (which is the one available in the repo).

API response example

For instance, the API response below contains a component hierarchy with two modules, page => post-feed, where module post-feed fetches blog posts. Please notice the following:

- Each module knows which are its queried objects from property

dbobjectids(IDs4and9for the blog posts) - Each module knows the object type for its queried objects from property

dbkeys(each post’s data is found underposts, and the post’s author data, corresponding to the author with the ID given under the post’s propertyauthor, is found underusers) - Because the database object data is relational, property

authorcontains the ID to the author object instead of printing the author data directly.

{

moduledata: {

"page": {

modules: {

"post-feed": {

dbobjectids: [4, 9]

}

}

}

},

modulesettings: {

"page": {

modules: {

"post-feed": {

dbkeys: {

id: "posts",

author: "users"

}

}

}

}

},

databases: {

primary: {

posts: {

4: {

title: "Hello World!",

author: 7

},

9: {

title: "Everything fine?",

author: 7

}

},

users: {

7: {

name: "Leo"

}

}

}

}

}

Differences Fetching Data From Resource-Based, Schema-Based And Component-Based APIs

Let’s see how a component-based API such as PoP compares, when fetching data, to a resource-based API such as REST, and to a schema-based API such as GraphQL.

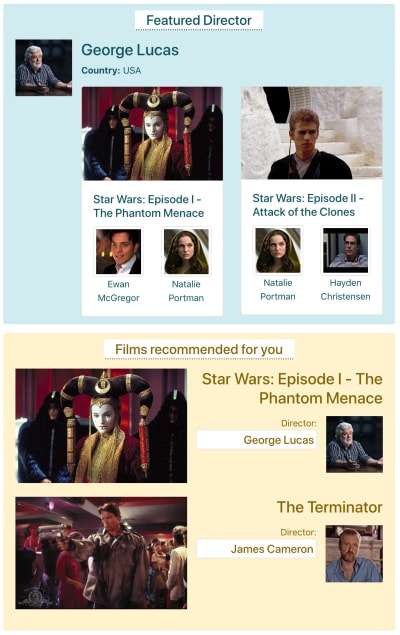

Let’s say IMDB has a page with two components which need to fetch data: “Featured director” (showing a description of George Lucas and a list of his films) and “Films recommended for you” (showing films such as Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace and The Terminator). It could look like this:

Components ‘Featured director’ and ‘Films recommended for you’ for the next-generation IMDB site. (Large preview)

Let’s see how many requests are needed to fetch the data through each API method. For this example, the “Featured director” component brings one result (“George Lucas”), from which it retrieves two films (Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace and Star Wars: Episode II — Attack of the Clones), and for each film two actors (“Ewan McGregor” and “Natalie Portman” for the first film, and “Natalie Portman” and “Hayden Christensen” for the second film). The component “Films recommended for you” brings two results (Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace and The Terminator), and then fetches their directors (“George Lucas” and “James Cameron” respectively).

Using REST to render component featured-director, we may need the following 7 requests (this number can vary depending on how much data is provided by each endpoint, i.e. how much over-fetching has been implemented):

GET - /featured-director

GET - /directors/george-lucas

GET - /films/the-phantom-menace

GET - /films/attack-of-the-clones

GET - /actors/ewan-mcgregor

GET - /actors/natalie-portman

GET - /actors/hayden-christensen

GraphQL allows, through strongly typed schemas, to fetch all the required data in one single request per component. The query to fetch data through GraphQL for the component featuredDirector looks like this (after we have implemented the corresponding schema):

query {

featuredDirector {

name

country

avatar

films {

title

thumbnail

actors {

name

avatar

}

}

}

}

And it produces the following response:

{

data: {

featuredDirector: {

name: "George Lucas",

country: "USA",

avatar: "...",

films: [

{

title: "Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace",

thumbnail: "...",

actors: [

{

name: "Ewan McGregor",

avatar: "...",

},

{

name: "Natalie Portman",

avatar: "...",

}

]

},

{

title: "Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones",

thumbnail: "...",

actors: [

{

name: "Natalie Portman",

avatar: "...",

},

{

name: "Hayden Christensen",

avatar: "...",

}

]

}

]

}

}

}

And querying for component “Films recommended for you” produces the following response:

{

data: {

films: [

{

title: "Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace",

thumbnail: "...",

director: {

name: "George Lucas",

avatar: "...",

}

},

{

title: "The Terminator",

thumbnail: "...",

director: {

name: "James Cameron",

avatar: "...",

}

}

]

}

}

PoP will issue only one request to fetch all the data for all components in the page, and normalize the results. The endpoint to be called is simply the same as the URL for which we need to get the data, just adding an additional parameter output=json to indicate to bring the data in JSON format instead of printing it as HTML:

GET - /url-of-the-page/?output=json

Assuming that the module structure has a top module named page containing modules featured-director and films-recommended-for-you, and these also have submodules, like this:

"page"

modules

"featured-director"

modules

"director-films"

modules

"film-actors"

"films-recommended-for-you"

modules

"film-director"

The single returned JSON response will look like this:

{

modulesettings: {

"page": {

modules: {

"featured-director": {

dbkeys: {

id: "people",

},

modules: {

"director-films": {

dbkeys: {

films: "films"

},

modules: {

"film-actors": {

dbkeys: {

actors: "people"

},

}

}

}

}

},

"films-recommended-for-you": {

dbkeys: {

id: "films",

},

modules: {

"film-director": {

dbkeys: {

director: "people"

},

}

}

}

}

}

},

moduledata: {

"page": {

modules: {

"featured-director": {

dbobjectids: [1]

},

"films-recommended-for-you": {

dbobjectids: [1, 3]

}

}

}

},

databases: {

primary: {

people {

1: {

name: "George Lucas",

country: "USA",

avatar: "..."

films: [1, 2]

},

2: {

name: "Ewan McGregor",

avatar: "..."

},

3: {

name: "Natalie Portman",

avatar: "..."

},

4: {

name: "Hayden Christensen",

avatar: "..."

},

5: {

name: "James Cameron",

avatar: "..."

},

},

films: {

1: {

title: "Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace",

actors: [2, 3],

director: 1,

thumbnail: "..."

},

2: {

title: "Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones",

actors: [3, 4],

thumbnail: "..."

},

3: {

title: "The Terminator",

director: 5,

thumbnail: "..."

},

}

}

}

}

Let’s analyze how these three methods compare to each other, in terms of speed and the amount of data retrieved.

Speed

Through REST, having to fetch 7 requests just to render one component can be very slow, mostly on mobile and shaky data connections. Hence, the jump from REST to GraphQL represents a great deal for speed, because we are able to render a component with only one request.

PoP, because it can fetch all data for many components in one request, will be faster for rendering many components at once; however, most likely there is no need for this. Having components be rendered in order (as they appear in the page), is already a good practice, and for those components which appear under the fold there is certainly no rush to render them. Hence, both the schema-based and component-based APIs are already pretty good and clearly superior to a resource-based API.

Amount of Data

On each request, data in the GraphQL response may be duplicated: actress “Natalie Portman” is fetched twice in the response from the first component, and when considering the joint output for the two components, we can also find shared data, such as film Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace.

PoP, on the other hand, normalizes the database data and prints it only once, however, it carries the overhead of printing the module structure. Hence, depending on the particular request having duplicated data or not, either the schema-based API or the component-based API will have a smaller size.

In conclusion, a schema-based API such as GraphQL and a component-based API such as PoP are similarly good concerning performance, and superior to a resource-based API such as REST.

Recommended reading: Understanding And Using REST APIs

Particular Properties Of A Component-Based API

If a component-based API is not necessarily better in terms of performance than a schema-based API, you may be wondering, then what am I trying to achieve with this article?

In this section, I will attempt to convince you that such an API has incredible potential, providing several features which are very desirable, making it a serious contender in the world of APIs. I describe and demonstrate each of its unique great features below.

The Data To Be Retrieved From The Database Can Be Inferred From The Component Hierarchy

When a module displays a property from a DB object, the module may not know, or care, what object it is; all it cares about is defining what properties from the loaded object are required.

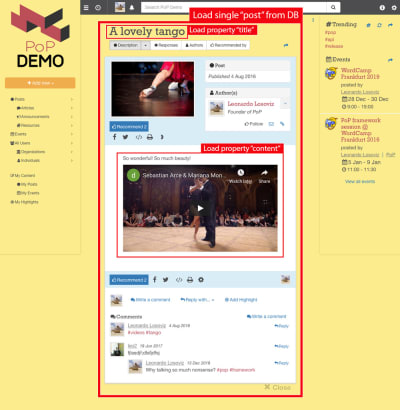

For instance, consider the image below. A module loads an object from the database (in this case, a single post), and then its descendant modules will show certain properties from the object, such as title and content:

While some modules load the database object, others load properties. (Large preview)

Hence, along the component hierarchy, the “dataloading” modules will be in charge of loading the queried objects (the module loading the single post, in this case), and its descendant modules will define what properties from the DB object are required (title and content, in this case).

Fetching all the required properties for the DB object can be done automatically by traversing the component hierarchy: starting from the dataloading module, we iterate all its descendant modules all the way down until reaching a new dataloading module, or until the end of the tree; at each level we obtain all required properties, and then merge all properties together and query them from the database, all of them only once.

In the structure below, module single-post fetches the results from the DB (the post with ID 37), and submodules post-title and post-content define properties to be loaded for the queried DB object (title and content respectively); submodules post-layout and fetch-next-post-button do not require any data fields.

"single-post"

=> Load objects with object type "post" and ID 37

modules

"post-layout"

modules

"post-title"

=> Load property "title"

"post-content"

=> Load property "content"

"fetch-next-post-button"

The query to be executed is calculated automatically from the component hierarchy and their required data fields, containing all the properties needed by all the modules and their submodules:

SELECT

title, content

FROM

posts

WHERE

id = 37

By fetching the properties to retrieve directly from the modules, the query will be automatically updated whenever the component hierarchy changes. If, for instance, we then add submodule post-thumbnail, which requires data field thumbnail:

"single-post"

=> Load objects with object type "post" and ID 37

modules

"post-layout"

modules

"post-title"

=> Load property "title"

"post-content"

=> Load property "content"

"post-thumbnail"

=> Load property "thumbnail"

"fetch-next-post-button"

Then the query is automatically updated to fetch the additional property:

SELECT

title, content, thumbnail

FROM

posts

WHERE

id = 37

Because we have established the database object data to be retrieved in a relational manner, we can also apply this strategy among the relationships between database objects themselves.

Consider the image below: Starting from the object type post and moving down the component hierarchy, we will need to shift the DB object type to user and comment, corresponding to the post’s author and each of the post’s comments respectively, and then, for each comment, it must change the object type once again to user corresponding to the comment’s author.

Moving from a database object to a relational object (possibly changing the object type, as in post => author going from post to user, or not, as in author => followers going from user to user) is what I call “switching domains”.

Changing the DB object from one domain to another. (Large preview)

After switching to a new domain, from that level at the component hierarchy downwards, all required properties will be subjected to the new domain:

nameis fetched from theuserobject (representing the post’s author),contentis fetched from thecommentobject (representing each of the post’s comments),nameis fetched from theuserobject (representing the author of each comment).

Traversing the component hierarchy, the API knows when it is switching to a new domain and, appropriately, update the query to fetch the relational object.

For example, if we need to show data from the post’s author, stacking submodule post-author will change the domain at that level from post to the corresponding user, and from this level downwards the DB object loaded into the context passed to the module is the user. Then, submodules user-name and user-avatar under post-author will load properties name and avatar under the user object:

"single-post"

=> Load objects with object type "post" and ID 37

modules

"post-layout"

modules

"post-title"

=> Load property "title"

"post-content"

=> Load property "content"

"post-author"

=> Switch domain from "post" to "user", based on property "author"

modules

"user-layout"

modules

"user-name"

=> Load property "name"

"user-avatar"

=> Load property "avatar"

"fetch-next-post-button"

Resulting in the following query:

SELECT

p.title, p.content, p.author, u.name, u.avatar

FROM

posts p

INNER JOIN

users u

WHERE

p.id = 37 AND p.author = u.id

In summary, by configuring each module appropriately, there is no need to write the query to fetch data for a component-based API. The query is automatically produced from the structure of the component hierarchy itself, obtaining what objects must be loaded by the dataloading modules, the fields to retrieve for each loaded object defined at each descendant module, and the domain switching defined at each descendant module.

Adding, removing, replacing or altering any module will automatically update the query. After executing the query, the retrieved data will be exactly what is required — nothing more or less.

Observing Data And Calculating Additional Properties

Starting from the dataloading module down the component hierarchy, any module can observe the returned results and calculate extra data items based on them, or feedback values, which are placed under entry moduledata.

For instance, module fetch-next-post-button can add a property indicating if there are more results to fetch or not (based on this feedback value, if there aren’t more results, the button will be disabled or hidden):

{

moduledata: {

"page": {

modules: {

"single-post": {

modules: {

"fetch-next-post-button": {

feedback: {

hasMoreResults: true

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

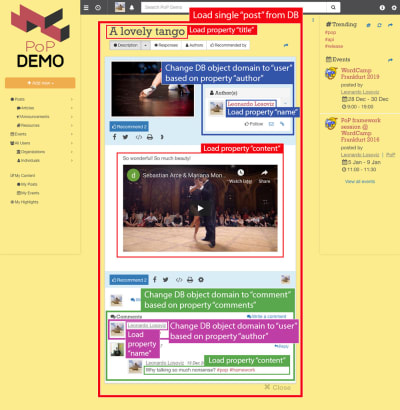

Implicit Knowledge Of Required Data Decreases Complexity And Makes The Concept Of An “Endpoint” Become Obsolete

As shown above, the component-based API can fetch exactly the required data, because it has the model of all components on the server and what data fields are required by each component. Then, it can make the knowledge of the required data fields implicit.

The advantage is that defining what data is required by the component can be updated just on the server-side, without having to redeploy JavaScript files, and the client can be made dumb, just asking the server to provide whatever data it is that it needs, thus decreasing the complexity of the client-side application.

In addition, calling the API to retrieve the data for all components for a specific URL can be carried out simply by querying that URL plus adding the extra parameter output=json to indicate returning API data instead of printing the page. Hence, the URL becomes its own endpoint or, considered in a different way, the concept of an “endpoint” becomes obsolete.

Requests to fetch resources with different APIs. (Large preview)

Retrieving Subsets Of Data: Data Can Be Fetched For Specific Modules, Found At Any Level Of The Component Hierarchy

What happens if we don’t need to fetch the data for all modules in a page, but simply the data for a specific module starting at any level of the component hierarchy? For instance, if a module implements an infinite-scroll, when scrolling down we must fetch only new data for this module, and not for the other modules on the page.

This can be accomplished by filtering the branches of the component hierarchy that will be included in the response, to include properties only starting from the specified module and ignore everything above this level. In my implementation (which I will describe in an upcoming article), the filtering is enabled by adding parameter modulefilter=modulepaths to the URL, and the selected module (or modules) is indicated through a modulepaths[] parameter, where a “module path” is the list of modules starting from the top-most module to the specific module (e.g. module1 => module2 => module3 has module path [module1, module2, module3] and is passed as a URL parameter as module1.module2.module3).

For instance, in the component hierarchy below every module has an entry dbobjectids:

"module1"

dbobjectids: [...]

modules

"module2"

dbobjectids: [...]

modules

"module3"

dbobjectids: [...]

"module4"

dbobjectids: [...]

"module5"

dbobjectids: [...]

modules

"module6"

dbobjectids: [...]

Then requesting the webpage URL adding parameters modulefilter=modulepaths and modulepaths[]=module1.module2.module5 will produce the following response:

"module1"

modules

"module2"

modules

"module5"

dbobjectids: [...]

modules

"module6"

dbobjectids: [...]

In essence, the API starts loading data starting from module1 => module2 => module5. That’s why module6, which comes under module5, also brings its data while module3 and module4 do not.

In addition, we can create custom module filters to include a pre-arranged set of modules. For instance, calling a page with modulefilter=userstate can print only those modules which require user state for rendering them in the client, such as modules module3 and module6:

"module1"

modules

"module2"

modules

"module3"

dbobjectids: [...]

"module5"

modules

"module6"

dbobjectids: [...]

The information of which are the starting modules comes under section requestmeta, under entry filteredmodules, as an array of module paths:

requestmeta: {

filteredmodules: [

["module1", "module2", "module3"],

["module1", "module2", "module5", "module6"]

]

}

This feature allows to implement an uncomplicated Single-Page Application, in which the frame of the site is loaded on the initial request:

"page"

modules

"navigation-top"

dbobjectids: [...]

"navigation-side"

dbobjectids: [...]

"page-content"

dbobjectids: [...]

But, from them on, we can append parameter modulefilter=page to all requested URLs, filtering out the frame and bringing only the page content:

"page"

modules

"navigation-top"

"navigation-side"

"page-content"

dbobjectids: [...]

Similar to module filters userstate and page described above, we can implement any custom module filter and create rich user experiences.

The Module Is Its Own API

As shown above, we can filter the API response to retrieve data starting from any module. As a consequence, every module can interact with itself from client to server just by adding its module path to the webpage URL in which it has been included.

I hope you will excuse my over-excitement, but I truly can’t emphasize enough how wonderful this feature is. When creating a component, we don’t need to create an API to go alongside with it to retrieve data (REST, GraphQL, or anything at all), because the component is already able to talk to itself in the server and load its own data — it is completely autonomous and self-serving.

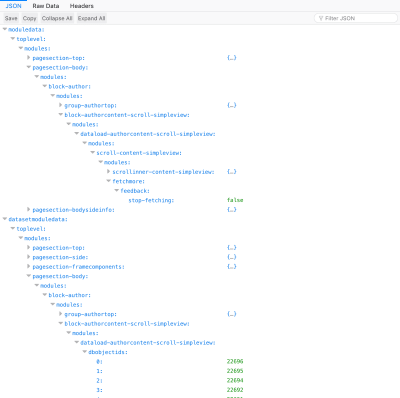

Each dataloading module exports the URL to interact with it under entry dataloadsource from under section datasetmodulemeta:

{

datasetmodulemeta: {

"module1": {

modules: {

"module2": {

modules: {

"module5": {

meta: {

dataloadsource: "https://page-url/?modulefilter=modulepaths&modulepaths[]=module1.module2.module5"

},

modules: {

"module6": {

meta: {

dataloadsource: "https://page-url/?modulefilter=modulepaths&modulepaths[]=module1.module2.module5.module6"

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Fetching Data Is Decoupled Across Modules And DRY

To make my point that fetching data in a component-based API is highly decoupled and DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), I will first need to show how in a schema-based API such as GraphQL it is less decoupled and not DRY.

In GraphQL, the query to fetch data must indicate the data fields for the component, which may include subcomponents, and these may also include subcomponents, and so on. Then, the topmost component needs to know what data is required by every one of its subcomponents too, as to fetch that data.

For instance, rendering the component might require the following subcomponents:

Render <FeaturedDirector>:

<div>

Country: {country}

{foreach films as film}

<Film film={film} />

{/foreach}

</div>

Render <Film>:

<div>

Title: {title}

Pic: {thumbnail}

{foreach actors as actor}

<Actor actor={actor} />

{/foreach}

</div>

Render <Actor>:

<div>

Name: {name}

Photo: {avatar}

</div>

In this scenario, the GraphQL query is implemented at the level. Then, if subcomponent is updated, requesting the title through property filmTitle instead of title, the query from the component will need to be updated, too, to mirror this new information (GraphQL has a versioning mechanism which can deal with this problem, but sooner or later we should still update the information). This produces maintenance complexity, which could be difficult to handle when the inner components often change or are produced by third-party developers. Hence, components are not thoroughly decoupled from each other.

Similarly, we may want to render directly the component for some specific film, for which then we must also implement a GraphQL query at this level, to fetch the data for the film and its actors, which adds redundant code: portions of the same query will live at different levels of the component structure. So GraphQL is not DRY.

Because a component-based API already knows how its components wrap each other in its own structure, then these problems are completely avoided. For one, the client is able to simply request the required data it needs, whichever this data is; if a subcomponent data field changes, the overall model already knows and adapts immediately, without having to modify the query for the parent component in the client. Therefore, the modules are highly decoupled from each other.

For another, we can fetch data starting from any module path, and it will always return the exact required data starting from that level; there are no duplicated queries whatsoever, or even queries to start with. Hence, a component-based API is fully DRY. (This is another feature that really excites me and makes me get wet.)

(Yes, pun fully intended. Sorry about that.)

Retrieving Configuration Values In Addition To Database Data

Let’s revisit the example of the featured-director component for the IMDB site described above, which was created — you guessed it! — with Bootstrap. Instead of hardcoding the Bootstrap classnames or other properties such as the title’s HTML tag or the avatar max width inside of JavaScript files (whether they are fixed inside the component, or set through props by parent components), each module can set these as configuration values through the API, so that then these can be directly updated on the server and without the need to redeploy JavaScript files. Similarly, we can pass strings (such as the title Featured director) which can be already translated/internationalized on the server-side, avoiding the need to deploy locale configuration files to the front-end.

Similar to fetching data, by traversing the component hierarchy, the API is able to deliver the required configuration values for each module and nothing more or less.

The configuration values for the featured-director component might look like this:

{

modulesettings: {

"page": {

modules: {

"featured-director": {

configuration: {

class: "alert alert-info",

title: "Featured director",

titletag: "h3"

},

modules: {

"director-films": {

configuration: {

classes: {

wrapper: "media",

avatar: "mr-3",

body: "media-body",

films: "row",

film: "col-sm-6"

},

avatarmaxsize: "100px"

},

modules: {

"film-actors": {

configuration: {

classes: {

wrapper: "card",

image: "card-img-top",

body: "card-body",

title: "card-title",

avatar: "img-thumbnail"

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Please notice how — because the configuration properties for different modules are nested under each module’s level — these will never collide with each other if having the same name (e.g. property classes from one module will not override property classes from another module), avoiding having to add namespaces for modules.

Higher Degree Of Modularity Achieved In The Application

According to Wikipedia, modularity means:

The degree to which a system’s components may be separated and recombined, often with the benefit of flexibility and variety in use. The concept of modularity is used primarily to reduce complexity by breaking a system into varying degrees of interdependence and independence across and ‘hide the complexity of each part behind an abstraction and interface’.

Being able to update a component just from the server-side, without the need to redeploy JavaScript files, has the consequence of better reusability and maintenance of components. I will demonstrate this by re-imagining how this example coded for React would fare in a component-based API.

Let’s say that we have a component, currently with two items: and , like this:

Render <ShareOnSocialMedia>:

<ul>

<li>Share on Facebook: <FacebookShare url={window.location.href} /></li>

<li>Share on Twitter: <TwitterShare url={window.location.href} /></li>

</ul>

But then Instagram got kind of cool, so we need to add an item to our component, too:

Render <ShareOnSocialMedia>:

<ul>

<li>Share on Facebook: <FacebookShare url={window.location.href} /></li>

<li>Share on Twitter: <TwitterShare url={window.location.href} /></li>

<li>Share on Pinterest: <InstagramShare url={window.location.href} /></li>

</ul>

In the React implementation, as it can be seen in the linked code, adding a new component under component forces to redeploy the JavaScript file for the latter one, so then these two modules are not as decoupled as they could be.

In the component-based API, though, we can readily use the relationships among modules already described in the API to couple the modules together. While originally we will have this response:

{

modulesettings: {

"share-on-social-media": {

modules: {

"facebook-share": {

configuration: {...}

},

"twitter-share": {

configuration: {...}

}

}

}

}

}

After adding Instagram we will have the upgraded response:

{

modulesettings: {

"share-on-social-media": {

modules: {

"facebook-share": {

configuration: {...}

},

"twitter-share": {

configuration: {...}

},

"instagram-share": {

configuration: {...}

}

}

}

}

}

And just by iterating all the values under modulesettings["share-on-social-media"].modules, component can be upgraded to show the component without the need to redeploy any JavaScript file. Hence, the API supports the addition and removal of modules without compromising code from other modules, attaining a higher degree of modularity.

Native Client-Side Cache/Data Store

The retrieved database data is normalized in a dictionary structure, and standardized so that, starting from the value on dbobjectids, any piece of data under databases can be reached just by following the path to it as indicated through entries dbkeys, whichever way it was structured. Hence, the logic for organizing data is already native to the API itself.

We can benefit from this situation in several ways. For instance, the returned data for each request can be added into a client-side cache containing all data requested by the user throughout the session. Hence, it is possible to avoid adding an external data store such as Redux to the application (I mean concerning the handling of data, not concerning other features such as the Undo/Redo, the collaborative environment or the time-travel debugging).

Also, the component-based structure promotes caching: the component hierarchy depends not on the URL, but on what components are needed in that URL. This way, two events under /events/1/ and /events/2/ will share the same component hierarchy, and the information of what modules are required can be reutilized across them. As a consequence, all properties (other than database data) can be cached on the client after fetching the first event and reutilized from then on, so that only database data for each subsequent event must be fetched and nothing else.

Extensibility And Re-purposing

The databases section of the API can be extended, enabling to categorize its information into customized subsections. By default, all database object data is placed under entry primary, however, we can also create custom entries where to place specific DB object properties.

For instance, if the component “Films recommended for you” described earlier on shows a list of the logged-in user’s friends who have watched this film under property friendsWhoWatchedFilm on the film DB object, because this value will change depending on the logged-in user then we save this property under a userstate entry instead, so when the user logs out, we only delete this branch from the cached database on the client, but all the primary data still remains:

{

databases: {

userstate: {

films: {

5: {

friendsWhoWatchedFilm: [22, 45]

},

}

},

primary: {

films: {

5: {

title: "The Terminator"

},

}

"people": {

22: {

name: "Peter",

},

45: {

name: "John",

},

},

}

}

}

In addition, up to a certain point, the structure of the API response can be re-purposed. In particular, the database results can be printed in a different data structure, such as an array instead of the default dictionary.

For instance, if the object type is only one (e.g. films), it can be formatted as an array to be fed directly into a typeahead component:

[

{

title: "Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace",

thumbnail: "..."

},

{

title: "Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones",

thumbnail: "..."

},

{

title: "The Terminator",

thumbnail: "..."

},

]

Support For Aspect-Oriented Programming

In addition to fetching data, the component-based API can also post data, such as for creating a post or adding a comment, and execute any kind of operation, such as logging the user in or out, sending emails, logging, analytics, and so on. There are no restrictions: any functionality provided by the underlying CMS can be invoked through a module — at any level.

Along the component hierarchy, we can add any number of modules, and each module can execute its own operation. Hence, not all operations must necessarily be related to the expected action of the request, as when doing a POST, PUT or DELETE operation in REST or sending a mutation in GraphQL, but can be added to provide extra functionalities, such as sending an email to the admin when a user creates a new post.

So, by defining the component hierarchy through dependency-injection or configuration files, the API can be said to support Aspect-oriented programming, “a programming paradigm that aims to increase modularity by allowing the separation of cross-cutting concerns.”

Recommended reading: Protecting Your Site With Feature Policy

Enhanced Security

The names of the modules are not necessarily fixed when printed in the output, but can be shortened, mangled, changed randomly or (in short) made variable any way intended. While originally thought for shortening the API output (so that module names carousel-featured-posts or drag-and-drop-user-images could be shortened to a base 64 notation, such as a1, a2 and so on, for the production environment), this feature allows to frequently change the module names in the response from the API for security reasons.

For instance, input names are by default named as their corresponding module; then, modules called username and password, which are to be rendered in the client as and respectively, can be set varying random values for their input names (such as zwH8DSeG and QBG7m6EF today, and c3oMLBjo and c46oVgN6 tomorrow) making it more difficult for spammers and bots to target the site.

Versatility Through Alternative Models

The nesting of modules allows to branch out to another module to add compatibility for a specific medium or technology, or change some styling or functionality, and then return to the original branch.

For instance, let’s say the webpage has the following structure:

"module1"

modules

"module2"

modules

"module3"

"module4"

modules

"module5"

modules

"module6"

In this case, we’d like to make the website also work for AMP, however, modules module2, module4 and module5 are not AMP compatible. We can branch these modules out into similar, AMP-compatible modules module2AMP, module4AMP and module5AMP, after which we keep loading the original component hierarchy, so then only these three modules are substituted (and nothing else):

"module1"

modules

"module2AMP"

modules

"module3"

"module4AMP"

modules

"module5AMP"

modules

"module6"

This makes it fairly easy to generate different outputs from a single codebase, adding forks only here and there as needed, and always scoped and restrained to individual modules.

Demonstration Time

The code implementing the API as explained in this article is available in this open-source repository.

I have deployed the PoP API under https://nextapi.getpop.org for demonstration purposes. The website runs on WordPress, so the URL permalinks are those typical to WordPress. As noted earlier, through adding parameter output=json to them, these URLs become their own API endpoints.

The site is backed by the same database from the PoP Demo website, so a visualization of the component hierarchy and retrieved data can be done querying the same URL in this other website (e.g. visiting the https://demo.getpop.org/u/leo/ explains the data from https://nextapi.getpop.org/u/leo/?output=json).

The links below demonstrate the API for cases described earlier on:

- The homepage, a single post, an author, a list of posts and a list of users.

- An event, filtering from a specific module.

- A tag, filtering modules which require user state and filtering to bring only a page from a Single-Page Application.

- An array of locations, to feed into a typeahead.

- Alternative models for the “Who we are” page: Normal, Printable, Embeddable.

- Changing the module names: original vs mangled.

- Filtering information: only module settings, module data plus database data.

Example of JSON code returned by the API. (Large preview)

Conclusion

A good API is a stepping stone for creating reliable, easily maintainable and powerful applications. In this article, I have described the concepts powering a component-based API which, I believe, is a pretty good API, and I hope I have convinced you too.

So far, the design and implementation of the API have involved several iterations and taken more than five years — and it’s not completely ready yet. However, it is in a pretty decent state, not ready for production but as a stable alpha. These days, I am still working on it; working on defining the open specification, implementing the additional layers (such as rendering) and writing documentation.

In an upcoming article, I will describe how my implementation of the API works. Until then, if you have any thoughts about it — regardless whether positive or negative — I would love to read your comments below.

(rb, ra, yk, il)

From our sponsors: Introducing The Component-Based API