Beyond The Browser: Getting Started With Serverless WebAssembly

Beyond The Browser: Getting Started With Serverless WebAssembly

Beyond The Browser: Getting Started With Serverless WebAssembly

Robert Aboukhalil

2019-08-28T13:30:59+02:00

2019-08-28T12:36:01+00:00

Now that WebAssembly is supported by all major browsers and more than 85% of users worldwide, JavaScript is no longer the only browser language in town. If you haven’t heard, WebAssembly is a new low-level language that runs in the browser. It’s also a compilation target, which means you can compile existing programs written in languages such as C, C++, and Rust into WebAssembly, and run those programs in the browser. So far, WebAssembly has been used to port all sorts of applications to the web, including desktop applications, command-line tools, games and data science tools.

Note: For an in-depth case study of how WebAssembly can be used inside the browser to speed up web applications, check out my previous article.

WebAssembly Outside The Web?

Although most WebAssembly applications today are browser-centric, WebAssembly itself wasn’t originally designed just for the web, but really for any sandboxed environment. In fact, there’s recently been a lot of interest in exploring how WebAssembly could be useful outside the browser, as a general approach for running binaries on any OS or computer architecture, so long as there is a WebAssembly runtime that supports that system. In this article, we’ll look at how WebAssembly can be run outside the browser, in a serverless/Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) fashion.

WebAssembly For Serverless Applications

In a nutshell, serverless functions are a computing model where you hand your code to a cloud provider, and let them execute and manage scaling that code for you. For example, you can ask for your serverless function to be executed anytime you call an API endpoint, or to be driven by events, such as when a file is uploaded to your cloud bucket. While the term “serverless” may seem like a misnomer since servers are clearly involved somewhere along the way, it is serverless from our point of view since we don’t need to worry about how to manage, deploy or scale those servers.

Although these functions are usually written in languages like Python and JavaScript (Node.js), there are a number of reasons you might choose to use WebAssembly instead:

Serverless providers that support WebAssembly (including Cloudflare and Fastly report that they can launch functions at least an order of magnitude faster than most cloud providers can with other languages. They achieve this by running tens of thousands of WebAssembly modules in the same process, which is possible because the sandboxed nature of WebAssembly makes for a more efficient way of obtaining the isolation that containers are traditionally used for.

One of the main appeals of WebAssembly in the browser is the ability to port existing code to the web without having to rewrite everything to JavaScript. This benefit still holds true in the serverless use case because cloud providers limit which languages you can write your serverless functions in. Typically, they will support Python, Node.js, and maybe a few others, but certainly not C, C++, or Rust. By supporting WebAssembly, serverless providers can indirectly support a lot more languages.

When running WebAssembly in the browser, we’re relying on the end user’s computer to perform our computations. If those computations are too intensive, our users won’t be happy when their computer fan starts whirring. Running WebAssembly outside the browser gives us the speed and portability benefits of WebAssembly, while also keeping our application lightweight. On top of that, since we’re running our WebAssembly code in a more predictable environment, we can potentially perform more intensive computations.

A Concrete Example

In my previous article here on Smashing Magazine, we discussed how we sped up a web application by replacing slow JavaScript calculations with C code compiled to WebAssembly. The web app in question was fastq.bio, a tool for previewing the quality of DNA sequencing data.

As a concrete example, let’s rewrite fastq.bio as an application that makes use of serverless WebAssembly instead of running the WebAssembly inside the browser. For this article, we’ll use Cloudflare Workers, a serverless provider that supports WebAssembly and is built on top of the V8 browser engine. Another cloud provider, Fastly, is working on a similar offering, but based on their Lucet runtime.

First, let’s write some Rust code to analyze the data quality of DNA sequencing data. For convenience, we can leverage the Rust-Bio bioinformatics library to handle parsing the input data, and the wasm-bindgen library to help us compile our Rust code to WebAssembly.

Here’s a snippet of the code that reads in DNA sequencing data and outputs a JSON with a summary of quality metrics:

// Import packages

extern crate wasm_bindgen;

use bio::seq_analysis::gc;

use bio::io::fastq;

...

// This "wasm_bindgen" tag lets us denote the functions

// we want to expose in our WebAssembly module

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub fn fastq_metrics(seq: String) -> String

{

...

// Loop through lines in the file

let reader = fastq::Reader::new(seq.as_bytes());

for result in reader.records() {

let record = result.unwrap();

let sequence = record.seq();

// Calculate simple statistics on each record

n_reads += 1.0;

let read_length = sequence.len();

let read_gc = gc::gc_content(sequence);

// We want to draw histograms of these values

// so we store their values for later plotting

hist_gc.push(read_gc * 100.0);

hist_len.push(read_length);

...

}

// Return statistics as a JSON blob

json!({

"n": n_reads,

"hist": {

"gc": hist_gc,

"len": hist_len

},

...

}).to_string()

}We then used Cloudflare’s wrangler command-line tool to do the heavy lifting of compiling to WebAssembly and deploying to the cloud. Once done, we are given an API endpoint that takes sequencing data as input and returns a JSON with data quality metrics. We can now integrate that API into our application.

Here’s a GIF of the application in action:

Instead of running the analysis directly in the browser, the serverless version of our application makes several POST requests in parallel to our serverless function (see right sidebar), and updates the plots each time it returns more data. (Large preview)

The full code is available on GitHub (open-source).

Putting It All In Context

To put the serverless WebAssembly approach in context, let’s consider four main ways in which we can build data processing web applications (i.e. web apps where we perform analysis on data provided by the user):

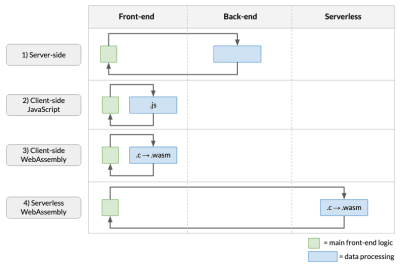

Four different architectural choices that we can take for apps that process data. (Large preview)

As shown above, the data processing can be done in several places:

This is the approach taken by most web applications, where API calls made in the front-end launch data processing on the back-end.

In this approach, the data processing code is written in JavaScript and runs in the browser. The downside is that your performance will take a hit, and if your original code wasn’t in JavaScript, you’ll need to rewrite it from scratch!

This involves compiling data analysis code to WebAssembly and running it in the browser. If the analysis code was written in languages like C, C++ or Rust (as is often the case in my field of genomics), this obviates the need to rewrite complex algorithms in JavaScript. It also provides the potential for speeding up our application (e.g. as discussed in a previous article).

This involves running the compiled WebAssembly on the cloud, using a FaaS kind of model (e.g. this article).

So why would you choose the serverless approach over the others? For one thing, compared to the first approach, it has the benefits that come with using WebAssembly, especially the ability to port existing code without having to rewrite it to JavaScript. Compared to the third approach, serverless WebAssembly also means our app is more lightweight since we don’t use the user’s resources for number crunching. In particular, if the computations are fairly involved or if the data is already in the cloud, this approach makes more sense.

On the other hand, however, the app now needs to make network connections, so the application will likely be slower. Furthermore, depending on the scale of the computation and whether it is amenable to be broken down into smaller analysis pieces, this approach might not be suitable due to limitations imposed by serverless cloud providers on runtime, CPU, and RAM utilization.

Conclusion

As we saw, it is now possible to run WebAssembly code in a serverless fashion and reap the benefits of both WebAssembly (portability and speed) and those of function-as-a-service architectures (auto-scaling and per-per-use pricing). Certain types of applications — such as data analysis and image processing, to name a few — can greatly benefit from such an approach. Though the runtime suffers because of the additional round-trips to the network, this approach does allow us to process more data at a time and not put a drain on users’ resources.

(rb, dm, yk, il)

From our sponsors: Beyond The Browser: Getting Started With Serverless WebAssembly